“You’re not my friend!” Makes your heart sink, right? We’re hearing this phrase at school, but it might not mean exactly the same thing to us as it does to the kids who are using it.

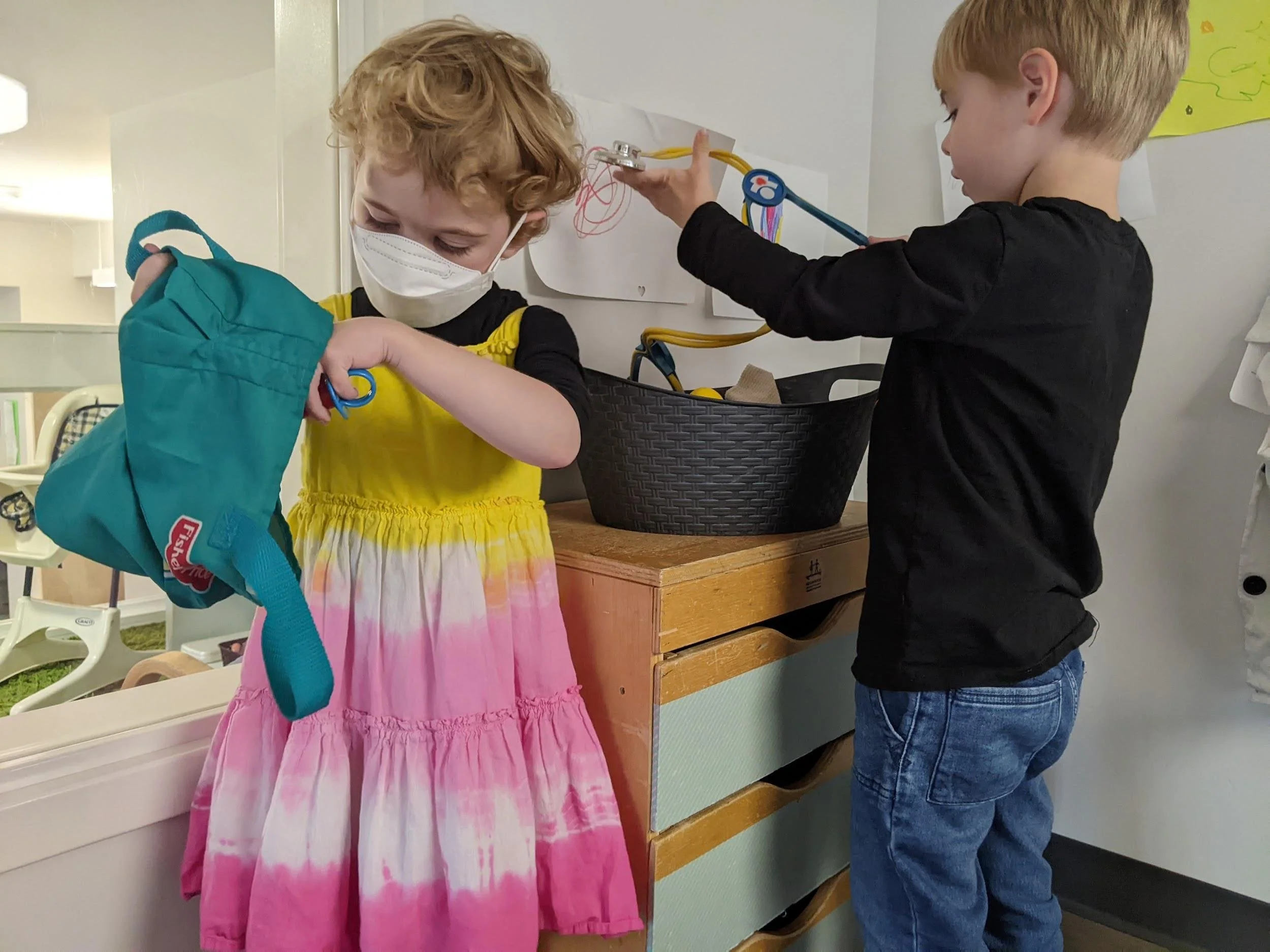

Developmentally, kids who are three and four have typically only just started to solidify their knowledge of the intricacies of working and playing with one other person. Negotiating and compromising, following someone else’s lead, and incorporating someone else’s ideas with your own are very big challenges. With such skills newly acquired, there is a lot of risk in trying to take them to the next level, small groups. This is one reason why we see such extreme defensiveness from some kids. They’re holding onto their relationship with the friend with whom they do feel confident taking risks and trying new ideas.

Here’s where it gets a little more complicated: kids are beginning to realize that they enjoy spending time with lots of other kids, in small groupings and in pairings. But, what do you do with that when you’ve only known friendship to be a concept you share with one other person? You accept someone as your friend when you want to do something with them, but reject them as your friend when you want to spend time with someone else or alone. That’s what friendship means to many kids right now: you are my friend when I am playing with you, you are not my friend when I’m not playing with you. So, most of the time kids are not trying to be hurtful when telling someone they are not their friend. It can be a matter of misunderstanding the complexities of friendship. Kids are still building this concept, and will continue to as long as they keep coming up against interactions and ideas that challenge and expand their preconceived notions.

There are times when someone has picked up on the fact that telling someone, “you’re not my friend,” hurts their feelings, and so they use the phrase to retaliate when they feel like they’ve been wronged, rather than as an exclusionary tactic. In this group, it happens when one’s preferred playmate is already engaged in play with another person and does not want to be joined by someone else. The one who is jealous of the relationship their preferred playmate has with someone else might tell them, “you’re not my friend,” in order to try to make them feel as bad as they do. Teachers try to help tease out what is going on in every situation in order to respond appropriately, and that begins by having a conversation with the kids who are involved.

We see the conversations we have with kids about what it means to be a friend to be beneficial for each person involved. When there is a conflict, we try to slow everyone down and really get to what is at heart for each person. We try to be free from judgment and ask simple questions like, “Did you say Matt is not your friend?” “You played with Matt in the gym today, and it looked like you were friends. Why not now?” Sometimes there are clues we can pick up on: a child’s eyes following another peer while trying to work through the conversation, or an existing play scenario with another person nearby. Then, we might ask something like, “Did you want to play with Sam right now instead of Matt?” or “Is Matt having a turn to play with Jason?”

Once we know what the motivation was, we can help work out a solution or compromise. “It’s okay to tell Matt that you want to play with Sam. Do you think you’ll want to play with Matt again another time?” Usually, the answer is yes, and we help work out a plan for when this will be. If not, we talk about why not. Sometimes feelings have been hurt on both sides and it’s not until the moments leading up to both are acknowledged that kids can move forward. Depending on where kids are developmentally, we might nudge someone a little more towards trying to incorporate another peer into play, but we’re not looking to move that faster than anyone is ready for. We think everyone needs time to master one-on-one play before moving into small group play. If there does seem to be malicious intent, we are clear about why this is not okay, but we still try to have a conversation about the motivations involved. Among other things, we see these conversations as opportunities for expanding emotional vocabulary, and offer new words to describe the nuanced feelings involved: “it sounds like you are jealous that she is playing with someone else, and it’s okay to tell her that” or “it looks like you are disappointed that she doesn’t want to play with you right now”.

Not everyone leaves these conversations happy. A lot of the time, someone is still hurt and has to then face the challenge of finding something else to do when they still want to be with their original choice. Teachers assist kids in this process with suggestions for other kids to be with or activities to try. And, there are times when someone is so overwhelmed by emotions that we suggest they just take a break from trying to be with someone else. We help them settle into another activity alone or with a teacher, and revisit the conversation about friendship after they’ve calmed down.

Our approach may look different to you from child to child, because it is. As with every point of development, each person is in a slightly different place; we respect that, and try to meet everyone where they are. We will be assessing and reassessing where each child is and what we can do to scaffold their development throughout the year.

When you hear about hurt feelings at home, comfort your child, but try to have a conversation about friendship too. You can use examples from your own life as models for the complexities of friendship: you and your partner probably don’t do everything together even though you love them, and maybe you have a friend you only see a few times a year, or one friend is fun to have dinner with, but you enjoy going to a museum with another. Reassure them that if they didn’t play with the pal they hoped to one day, they might the next, and ask questions about what they did do that day. Try not to fuel their hurt with your worry. If you think we’re unaware of something that is causing your child pain and confusion, write us a note or give us a call and we can observe their peer interactions more closely and follow-up with you.